Photo by Bill Hayward

Photo by Bill Hayward

Interview with Claire Donato

by Julie Sokolow

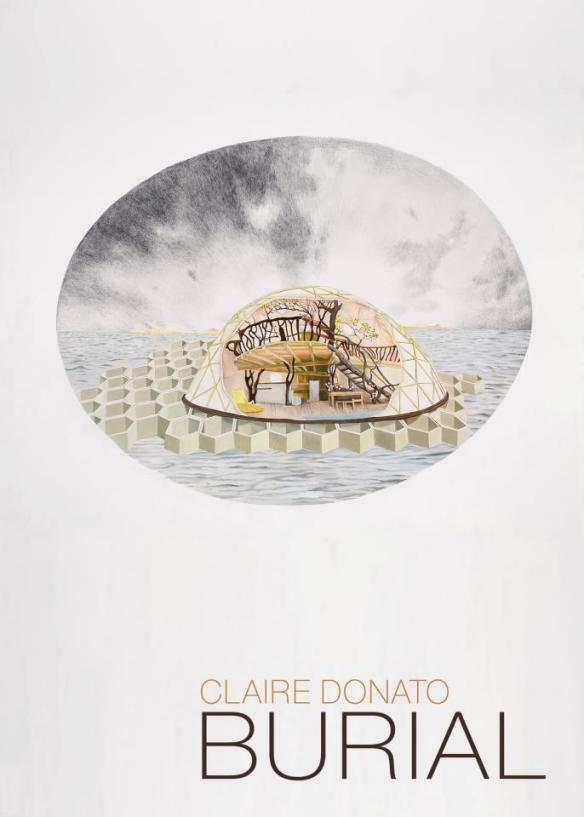

Claire Donato is an award-winning 26-year-old poet living in Brooklyn, NY. In 2010, she achieved an MFA at Brown University, where she was the first poet to ever win the John Hawkes Prize in Fiction. Her debut novel Burial was recently published by Tarpaulin Sky Press and named among the “Best Summer Reads 2013” by Publishers Weekly. The book is set in the mind of a narrator who is grieving the loss of her father, who conflates her hotel with the morgue. It’s been heralded as “enlightened,” “brave,” and “genre-bending.”

Donato’s work has appeared in places such as Boston Review, LIT, and Encyclopedia. She is the author of a poetry chapbook, Someone Else’s Body (Cannibal Books), and was a finalist for the National Poetry Series. She currently teaches at Fordham University and the School of Visual Arts.

We got a chance to revel with Donato, one of our favorite Pittsburgh natives, on topics such as academia and writing; creativity and wellness. As an avid runner and certified yoga teacher, Donato’s literary practice is complimented by an attention to physical health. We were eager to ask Donato about her poetic process as well as her thoughts on health care in America, informed by her personal health care story.

“The kindest poet lives alone. / A poet curls into himself. He looks at the ceiling and contributes / strange, pessimistic musings during conversation.”

from The Poet Said Those Years She Felt Depressed

HEALTHY ARTISTS: What inspires your sense of humor as you contemplate the poet’s role in contemporary society?

CLAIRE DONATO: Sometimes, it seems poets exist in vacuums. Within these vacuums, they absorb and enact stereotypes: Poets are anxious! Poets are cool! Poets are drunks! Poets are recovering! Poets are sensitive! Poets are demonstrative! Poets are poor! Poets are bourgeois bohemian! Poets are conservative! Poets are radical! Poets are prose-challenged! This behavior is reinforced through historical mythologies surrounding different schools of poetry.

The poet-writers I most appreciate consider expansive notions of writing and identity and engage with literature from multiple cultural, historical, and linguistic perspectives. American and international literatures coexist, informing one another’s worlds. When I imagine this expanded field, I think of an open space where writing shape-shifts beyond geographic limits (cf. Jennifer DeVere Brody), and takes place both on and off the physical page. These days, I am trying to think of myself less as a poet in New York and more as a writer in the world.

How is the intensely romanticized NY arts and literary scene treating you?

New York is unique in that there are innovative arts events happening every night. It can be difficult to balance outings alongside one’s own writing practice. Fortunately, I’m a bit of a homebody who loves staying in and working on a Friday evening.

The New York scene is also distinctive insofar as one can learn from highly skilled artists in other disciplines. I take yoga classes here about five days a week, and my practice has deepened under the guidance of teachers for whom yoga is not only a spiritual practice, but also an embodied form of art that requires precision, intelligent alignment, and grace.

“To the person who believes that light symbolizes all that’s good and draped across this / world: One should believe ancient myths contradict the way things are.”

from Manifesto La Terre / Mori

You got your MFA at one of the top five programs in the country. Did the experience live up to the reputation?

As a rule, I am skeptical of university rankings. That said, Brown gave me the world. I was paid to write for two years, gained experience teaching poetry workshops, and was encouraged to explore freely across genre boundaries. I was admitted to Brown as a poet, but studied and wrote fiction, electronic literature, and lyric essays. A RISD student and I collaborated on sculpture-based writing. I created site-specific installations of typewritten text around my neighborhood, the Armory. I learned from incredible writers and thinkers such as C.D. Wright, Keith Waldrop, and John Cayley; I attended school with writers such as Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi and Justin Katko, whose work, ethics, and imaginations I deeply admire.

Can you talk about being a member of the “Fakulty” at “Underacademy College”?

UnderAcademy College is an unaccredited, anti-degree institution. We accept everybody. It is a shadow-academic environment that offers alternative courses and anti-degree programs in a variety of subjects.

In short, UnderAcademy offers free online classes to anyone who wants to take them. These classes are often pataphysical (consult French absurdism). I recently taught ‘Entropy, Inertia, and Other Anti-Kinetics: A Feminist Way of Looking,’ a course loosely structured around men, dysfunction, and tedium, and ‘Diskinetics: Inner Yoga, Mental Gymnastics, and Metaphysical Education,’ a course emphasizing mental energy over muscular strength via studies of yogic inversions, levitation, and aquatic locomotion.

What do you anticipate will happen to form and genre distinctions in the future?

Brown recently introduced a cross-genre focus, and more and more students seem to be moving across/around/against/between genre boundaries. I suspect genre distinctions will continue to collapse. I think a lot about genre―and genre trouble (cf. Judith Butler). Genre, from the French, denotes “kind” and is etymologically linked to gender. I am in a constant conversation with myself about the pros and cons of genre, and depending on the day, I think of genre (and gender) classifications as a blessing and/or a plight. As long as we continue to sort our lives into “kinds”, genre distinctions will continue. One of my goals as a writer is to unsettle genre expectations and blur aesthetic boundaries that are linked to social relations at large.

“Check into the morgue with a bright yellow suitcase, a bag of dry rice, and a digital camera. Check into the morgue wearing wild alpaca: drafts of air ring out in one faint call. Check into the morgue stale from thinking. Think, ‘If TV drones out life, then life must be dead already’ and ‘If life is dead already, shouldn’t death already know?’”

from Burial

Can you talk about the process of writing Burial?

Burial took me about two years to write. Its topic and perspective emerged as I experimented with composing prose about and around hotels, morgues, caskets, and flowers, all important images in the book. From these images, the narrator came to be as a first-person ‘I,’ and the book’s concept followed suit. But the narrator’s ‘I’ did not feel productive to me in relation to grief: I wanted to craft a more intricate and dissociative perspective. So I experimented with creating a first-person narrative without ‘I’. Much of this experimentation involved physically retyping the book’s entire first draft, eliminating the ‘I’ sentence by sentence. It also involved reading a wealth of literature—particularly international literature—in which narrative conventions are disrupted.

What is your advice for writers on balancing poetic language with lucidity?

Lucidity comes with patience, which means writing a lot, making mistakes, and revising. In my experience, however, quantity, error, revision, and even writing are subjective―one can think writing a page a week is writing a lot; one can consider an image successful while another does not.

My first bit of advice for anybody who wants to write is to trust your own intuition. And intuition, I believe, can be honed. One way I try to hone my own intuition is through yoga and meditation. Observing my mind and body helps me better understand my mental and physical habits, loops, preoccupations, and sticky spots, which all inform my writing practice. Seeing my body and mind’s patterns has allowed me to both consciously engage with them, and let them go when need be.

“The night you leave, I write tourist across my stomach with regard / to everything I’ve ever done.”

from There are apologies I am too

What is SPECIAL AMERICA?

Special America is a collaboration between writer Jeff T. Johnson and myself. As a staged performance, it consists of multiple digital projections presented alongside appropriated musical loops and remixes that propel the performance through various scenes, acts, and interludes. Our script―whose language is appropriated from sources as wide-ranging as Robert Burton, Jacques Derrida, Andrew Lloyd Weber, and Rosmarie Waldrop―is delivered using heightened-affect character voices inspired by voiceover reels.

The staging, choreography, and costuming embody our theoretical concerns, which relate to American exceptionalism. For example, we most recently donned all-black clothing and black-and-white mime makeup, and mounted a yoga sequence, a wine tasting, a faux-academic panel, and various dances, including a formal dance and a YouTube-inspired rendition of the Twin Peaks character Audrey Hornes’s iconic solo dance.

At academic conferences, SPECIAL AMERICA presents itself as an analog hack or meme, a gesture toward embodied viral media. One of our goals is to imbue humor and play into academic conferences without sacrificing the rigor of our theoretical framework, an exercise in and an exorcism of notions of American Exceptionalism, based on the spirit of intellectual play.

Do you think writers/artists have a responsibility to be politically active?Language is inherently political. Writing embodies representations of the world – or, at the very least, the way someone’s mind functions within it. Writing can free up one’s creativity and empathetic capabilities, which can in turn alter the way s/he sees and moves responsibly within the world.

Yet I don’t believe that writers have a responsibility to craft work about concrete, political topics. One’s preoccupations with political issues―or lack thereof―will undoubtedly reverberate through one’s work. I do believe, however, that writers have a responsibility to create work that engages with empathy, a concept that can take on many different shapes. For example, my own personal exploration of empathy in writing is linked to a destabilized ‘I’ voice, attempts to see through multiples ‘I’s, and thus fluctuates.

In terms of political activity, poets and artists have a lot to be active about: low-paying adjunct gigs with no health benefits, cuts to arts programming in public schools, fewer and fewer government grants for artistic creation―the list goes on. And yet, of course, many of us are underpaid and overworked, so the ways our activism plays out vary. For me, activism is a key player in my classroom, where I actively work to connect my students with their own empathetic and generous capabilities.

“The night we met, I contracted a childhood disease. / The discoloration resembled that of tumeric or a fig tree.”

from Catalog Entry for Aging

Have you ever struggled with access to health care?

After I graduated from Brown, I started my first real post-MFA job. I was teaching as a faculty member for an intensive summer writing program at The New School. As a recent MFA graduate, I was generally exhausted, scared and stressed out, wading in a miniature existential plight, to say the least. At The New School, I taught five hours a day, five days a week – but not for long!

Soon, what I thought was a summer cold morphed into a terrible bout of pneumonia. I foolishly put off going to the doctor, because I was uninsured and lacking funds at the time. I still lack funds, but at least I now have COBRA insurance. Needless to say, once a friend convinced me to go to the doctor, an x-ray revealed an abscess in my lung. The medical bills added up fast. One bottle of medicine cost over $200. Within a week, I had spent over $1,000 on appointments and medicine. The irony of this situation is that, had I been insured, I would’ve gone to a doctor’s office the moment I came down with an abnormal cough.

What is your perspective on health care in America?

My mother is French, so I grew up believing every citizen should have equal access to health care—that this is a human right. When I was a teenager, I came down with chicken pox while visiting her family in France, and it was amazing how efficient the universal health care system was there. I saw a doctor, received medicine, and we did not have to pay anything, thanks to the country’s government-owned and operated clinics. Vermont has the right idea when it comes to pursuing single-payer universal health care. I hope it catches on in the rest of the US.

Claire Donato is currently working on her second novel Noël, which is a meditation on existence via the interior monologue of Noël, AKA No, who tries to imagine a world without her in it.

Claire Donato is currently working on her second novel Noël, which is a meditation on existence via the interior monologue of Noël, AKA No, who tries to imagine a world without her in it.

She will be reading Burial through May 2014 in cities such as Providence, Boston, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and New York. Get your copy at Tarpaulin Sky Press.

Learn more about her work at her website somanytumbleweeds.com. Connect with Donato on Twitter or Facebook.

One Pingback